Stop Using Dictionaries for Everything: Why Dataclasses are the Better Choice

You start a Python project. It’s small enough, so you store important data about users or products in a dictionary. As the project grows, you continue to ask yourself: “Was the key name or username? Is id a string or an int?”

As your model of users and products grows, you realize you’re validating data types and structures everywhere in your code, and the duplication is running amok. Dictionaries are super flexible, making them helpful problem-solvers in Python. They’re blind, however, to your data structure, making it difficult to use them for defined objects at scale.

Perhaps writing a class is better for representing these objects. Oh, it certainly is! If the data required to be stored needs type validation, or you ever need to compare object equality, as an example, you’ll find yourself writing repetitive code, which you should also solve.

Lucky for us, Python introduced dataclasses in 3.7 (yes, they’ve been around for several years now!) to provide the vision and guardrails needed for professional code.

What are dataclasses, actually?

A Python dataclass is a decorator that automatically generates boilerplate dunder-methods like __init__, __repr__, and __eq__, significantly reducing repetitive code when creating a class. As the name suggests, this is especially helpful for classes whose primary function is to store data.

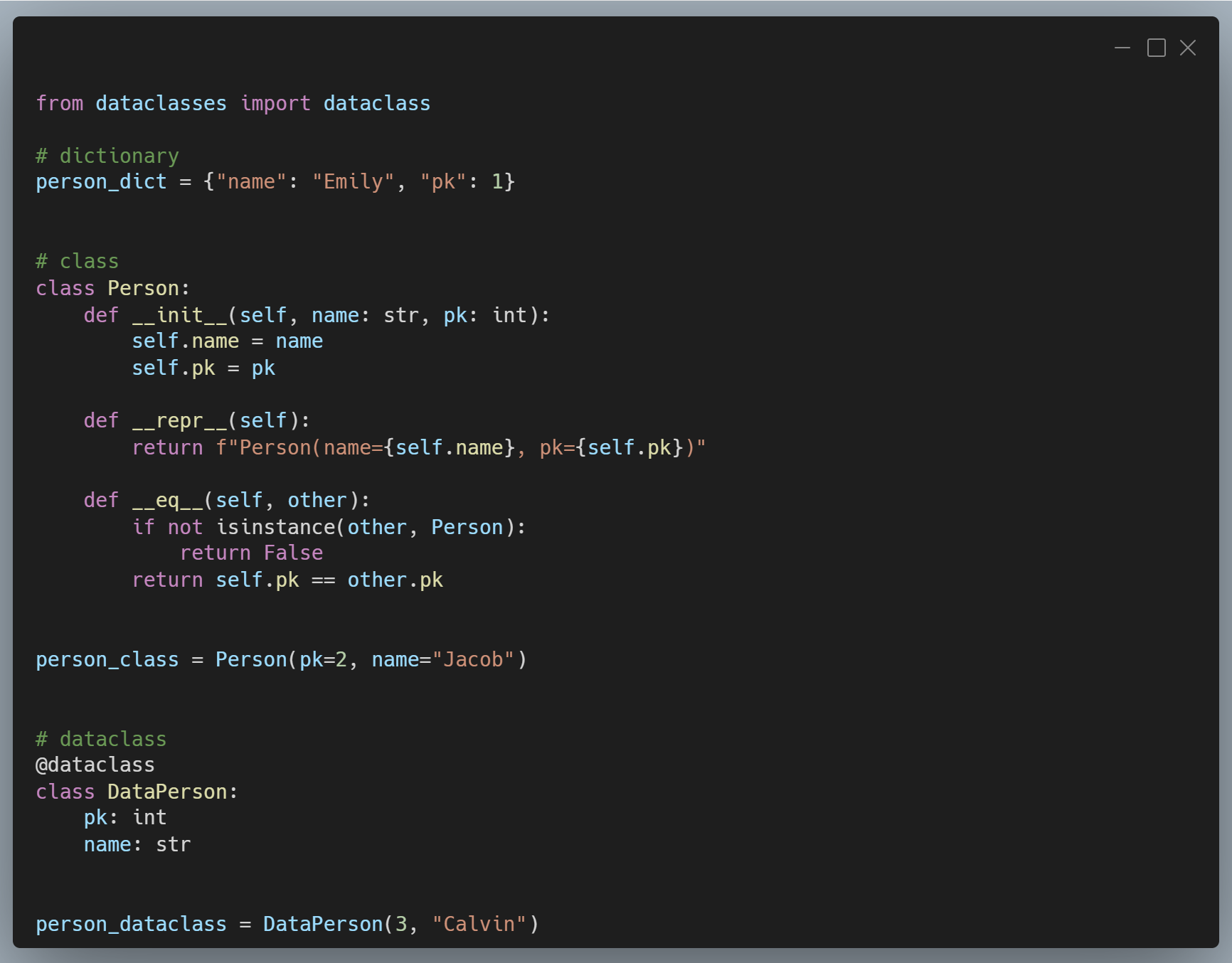

Let’s take a look at an example.

Defining a dictionary is straightforward enough. You set up the key value pairs for that particular instance of the “object” you’re trying to create. If you wanted to define another instance, you’d make a new dictionary and need to be sure to enter all of the keys and types the same way the next time, or else you’ll get a KeyError. More on that in a moment.

The difference between defining a class and a dataclass should be stark enough. Defining an ordinary class requires you to configure the dunder-methods essential to the function of that class. Because the class primarily defines a piece of data, the init, repr, and eq methods are described above.

The dataclass decorator does all of that for you, making it much quicker and less verbose to create a class with all of the functionality built in.

But, wait, there’s more!

Data access pattern & autocompletion

When you access data from a dictionary, you can either use the .get() method to return a default value, or access it with square brackets and the key name.

print(person_dict.get("name", "Nobody")) # returns "Emily"

# or

print(person_dict["pk"]) # returns 1If you decide to access with square brackets, you’ll need to be careful. If you misspell the key or if it doesn’t exist in the dictionary, a KeyError is raised. Handle it carefully, or your application will crash.

Accessing values with dataclasses uses dot-notation. Type in the instance of the dataclass followed by a period and the name of the attribute, and voila, you accessed the value.

But Jacob, don’t you have the same problem of hitting an error if you type the attribute name wrong?

If you typed the name of the attribute wrong, an AttributeError is raised. Unless you’re using Microsoft Notepad and have no linting, you won’t even commit that code. Your IDE will yell at you that you’re trying to access an attribute that does not exist. This differs from a dictionary, where typing in the wrong key name is totally acceptable.

More than your IDE yelling at you, by defining the dataclass in the first place, your IDE will now understand and “self-document” the object, so when you or a team member goes to use that dataclass, it’s painfully obvious with auto-complete what attributes are required and available.

Data validation & type safety

Dictionaries are “schema-less.” They are happy to let you store a string where an integer should be, or a negative number where a price should be positive. By the time you realize the data is wrong, it’s usually three functions deep and throwing a cryptic error.

With dataclasses, you can catch these issues at the front door.

Type Hinting as a Contract

While Python doesn’t enforce types at runtime by default, using dataclasses creates a contract. When you define id: int, you are telling every other developer (and your linting tools) exactly what to expect. If you use a tool like Mypy, it will flag any attempt to pass a string into that id field during your CI/CD process.

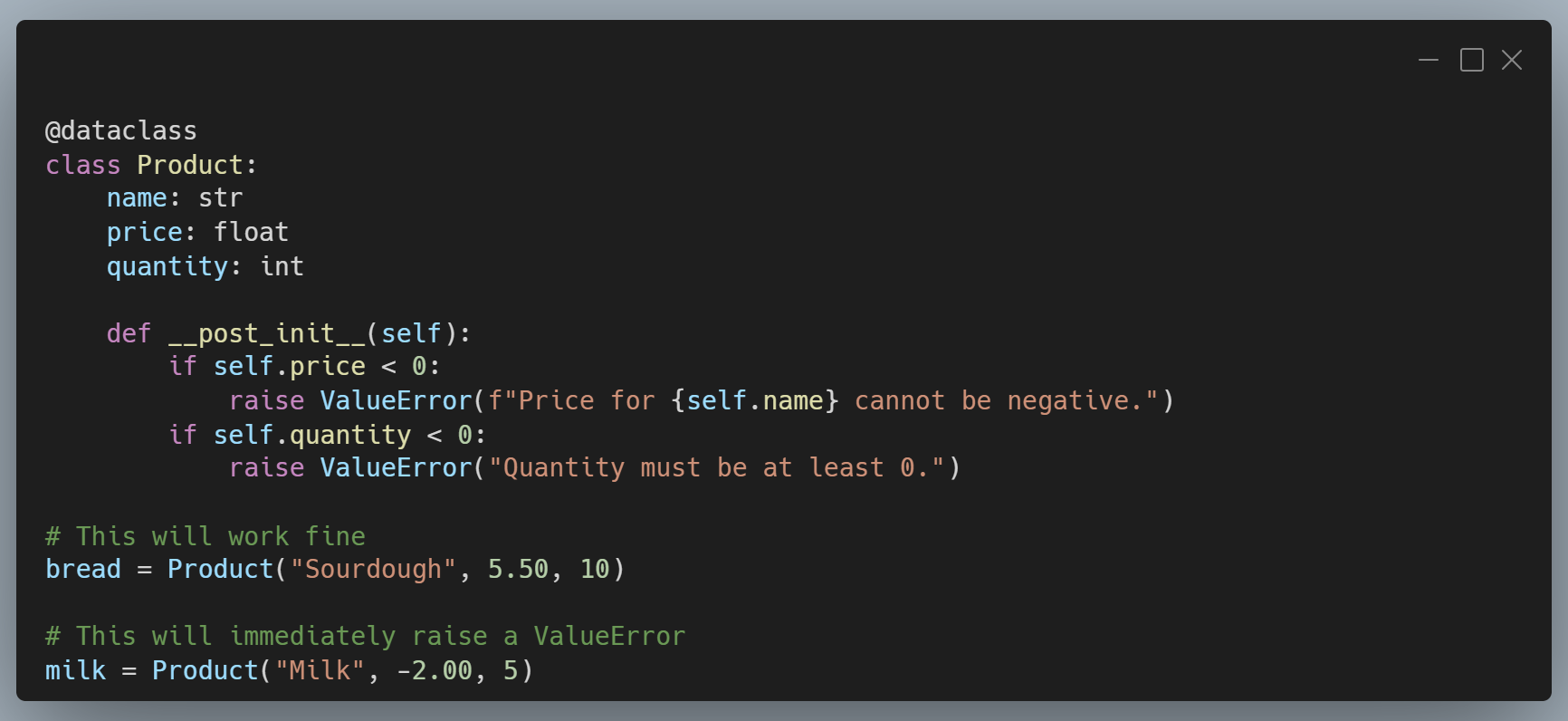

The Magic of __post_init__

Sometimes type hints aren’t enough. What if you need to ensure a product’s price isn’t negative? In a dictionary, you’d have to write a validation function and remember to call it every time you create a new dict.

In a dataclass, you can use the __post_init__ method. This method runs automatically right after the __init__ finishes.

By putting this logic inside the dataclass, you’ve created a single source of truth. You no longer have to hunt through your codebase to find where validation happens. Instead, it’s baked right into the definition of the data itself.

Conclusion

Moving to dataclasses is a minor syntax change that yields a massive leap in code quality. The next time you start passing dictionaries around your codebase, consider reaching for dataclasses instead.

Happy coding! 😁