Schema evolution for pragmatists

BEEP. BEEP. BEEP. The sound of your alarm at 2 AM is deafening. You wake up in a cold sweat, knowing that it's way too early to be getting up for the day, and it can only mean one thing: one of your critical data pipelines has failed, and you're on call.

You stumble to your computer, still half asleep. The light from your computer is blinding at first, but your eyes adjust quickly as you start looking at the logs to identify the failure. Then you see it…

The dang source system's schema has changed, and your pipeline failed because you didn't account for schema evolution. A flurry of thoughts races through your head:

- Schema evolution wasn't in the requirements!

- Why would they change the schema for this table anyway?

- Why didn't the source system team alert us that they'd be modifying the database table?

None of that helps now. You quickly fix the pipeline and table to account for the schema change, it runs successfully, and you head back to bed, full of anxiety that it'll happen again.

The Next Morning

Knowing that you don't want to get up at 2 AM again for the same problem, you start putting together a plan to answer the question of what to do when an upstream system modifies its schema.

Your first inclination was process: If an upstream system's schema is going to change, darn it, they should tell us! You talk to your manager, who rationalizes that having this sort of dependency between the upstream app team and the data team will create bottlenecks the business can't afford.

Back to the drawing board, and this time, you're thinking of only what's in your control. What can you change as a part of your data pipelines that will solve this problem?

You took account of your own "blast radius." Not all schema changes are created equal, and not all of them deserve a 2 AM wake-up call. You break down your options into three schema evolution patterns.

Patterns of Schema Evolution

First, a head-in-the-sand style approach. I.e., you just ignore it. If a column is added in the source system, it's not even considered in the table that gets staged. If a column is removed, you simply treat that column with NULL values going forward. To make any changes to the table in your lakehouse, you need to get it backlogged and configured. No failures in the middle of the night, but no automatic schema evolution either.

The second option you call the brick wall. In this pattern, you use strict schema validation to stop the data pipeline the moment a change is detected. If a change is detected and critical, this pattern ensures you know about it. Alarms go off in the middle of the night, and it's critical to business operations. In other words, it's a design choice; a feature, not a bug.

The final option you present is the bridge. This option automatically versions your table and updates the schema based on the source system. While more technically involved, it solves the problem of schema evolution without you needing to get involved, and ensures the downstream reports don't miss a beat. The downside? Schema evolution is happening with a code promotion.

Pro-Tip: If you go with the bridge pattern, ensure you have alerting without failing. You want a Slack/Teams notification saying "Schema evolved: New column 'discount_code' added," so you can update your documentation/logic during business hours, even though the pipeline didn't crash.

From Pattern to Implementation

After conversing with your fellow data engineers and architects, you agree that you're going to impose a combination of the head-in-the-sand and brick-wall patterns, based on the criticality of the pipeline. Head in the sand is straightforward enough: you're ignoring changes and adding NULLs where columns get dropped.

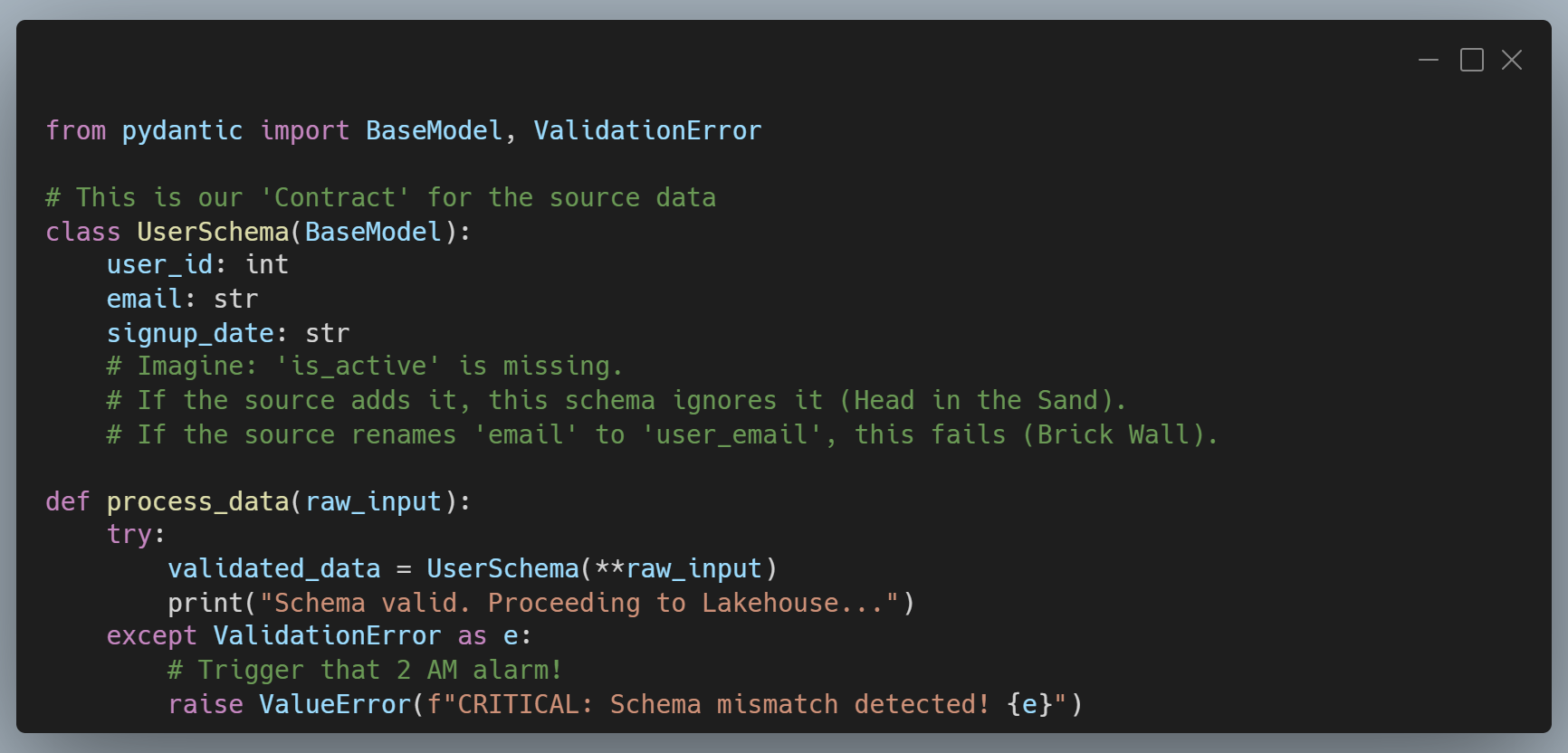

To implement the brick wall pattern, you decide to use Pydantic in your data pipelines for strict validation. By defining a "Contract Class," you force the pipeline to error out the second the incoming JSON or DataFrame doesn't match your expectations. It's the programmatic way of saying, "I refuse to process garbage."

In the example above, you actually allow new columns to be there. The key is that you're enforcing column expectations, i.e., the columns that you expect to be there are there. If you wanted to throw an error in the event of a new column, you could add this to your UserSchema class.

model_config = ConfigDict(extra='forbid')Building "Shock Absorbers"

As a Principal Architect, my job isn't to build a system that never changes. That's an impossible goal. My job is to build a system that is cheap to change.

Choosing between the Head in the Sand, the Brick Wall, or the Bridge depends entirely on your business's tolerance for risk:

- Use the Head in the Sand for low-stakes data where a missing column won't break the CEO's dashboard.

- Use the Brick Wall for financial or compliance data where accuracy is more important than uptime.

- Use the Bridge for high-scale, mature products where the "show must go on" regardless of upstream tinkering.

The next time your alarm goes off at 2 AM, don't just fix the column name. Ask yourself which pattern you're actually using, and whether it's time to upgrade your "shock absorbers."

Your sleep and your sanity depend on it.

As always, you can review the code in this post on GitHub. Happy coding! 😁