Factories are friends

You ever get so lost in thought about design patterns that your conversation partner says they've got to go to the bathroom, only to find out that they just wanted out of there so bad because you've been blabbering nonsense for 10 minutes flat? No? Oh, *clears throat*...

Anyway, I love design patterns in engineering. And how could you not? They solve regularly occurring problems in software development. A "best practice," if you will, or a template for what could otherwise be messy, unscalable code.

To that end, I'll be starting a series on software engineering design patterns. The first design pattern I'm diving into is a creational pattern: the factory method.

Note: If you want to look at any of the code from the pictures below, feel free to check them out in GitHub.

Creational design patterns

Design patterns are organized into a few groups depending on the problem they solve. There are creational, structural, and behavioral design patterns.

The factory method is a creational design pattern, but what exactly is this group of patterns? As the name implies, creational patterns create objects. They attempt to separate an application from how objects are created or combined in order to increase the modularity, and thus flexibility, of object creation.

Creational design patterns are particularly helpful when you...

- Want the code to depend on interfaces, not concrete classes.

- Want to hide the implementation of certain objects so that consumers have an easier time using your code.

- Want a class to create instances of its subclasses

- and more!

Now, let's get concrete about the problem we are trying to solve with the factory method.

The problem

Let's suppose that you're a data engineer, and you need to process different types of files: CSVs, JSON, parquet files, etc. One way you might implement this is to write functions, one for each file type, and create an if/elif/else chain like so.

If this code never changes and there aren't any new file types that need to be added, then wonderful! No need to change anything about this code. That's not the world we operate in, however. Instead, there will be new requirements:

- There's a new file type we need to load in

- We need finer control over loading CSV files

- We need to implement an extra step for loading all file types

While we could edit the functions defined above, we're updating the implementation (or application) of the data loading, rather than allowing the application code to abstract away the initialization of the data.

This leads to tight coupling, making the whole system harder to change, extend, and test.

Insert factory method

The factory method solves the problem of hard-coding object creation, making your system flexible, testable, and extensible.

The factory method is a creational design pattern that:

- Defines a method in a base class for creating objects.

- Let subclasses decide which concrete class should be instantiated.

In other words, the factory method moves object creation into a method that subclasses can override. This prevents the base class from being tightly coupled to specific object types.

The structure of the factory method design pattern looks like this:

- Creator (Base class) — Contains a factory method that returns a product.

- Concrete Creator (Subclass) — Overrides the factory method to instantiate specific products.

- Product (Interface/Class) — A common interface/type for the objects being created.

- Concrete Product — The actual object created.

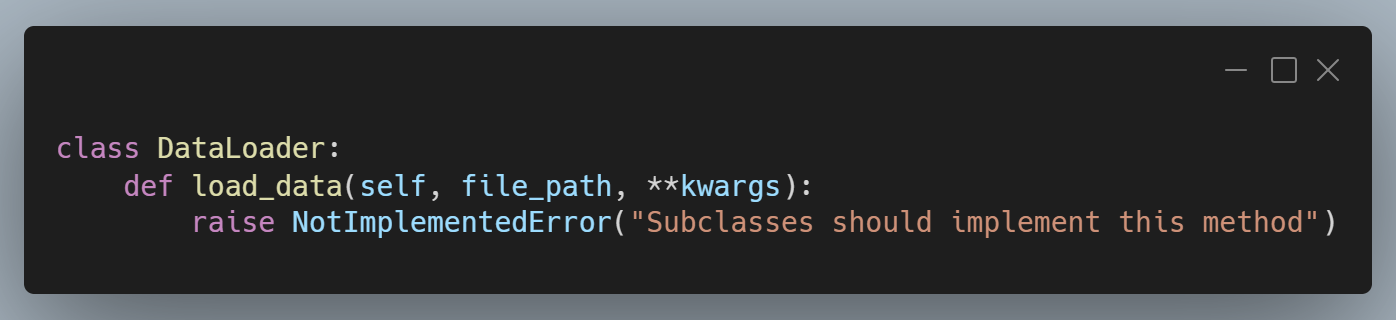

With this mental model in mind, let's turn back to our data ingestion problem. First, let's define how we want to call every load_* method. For now, we only need to pass in the file_path argument, but to ensure that this works if we want to add configuration options based on the file type later, we'll add optional **kwargs.

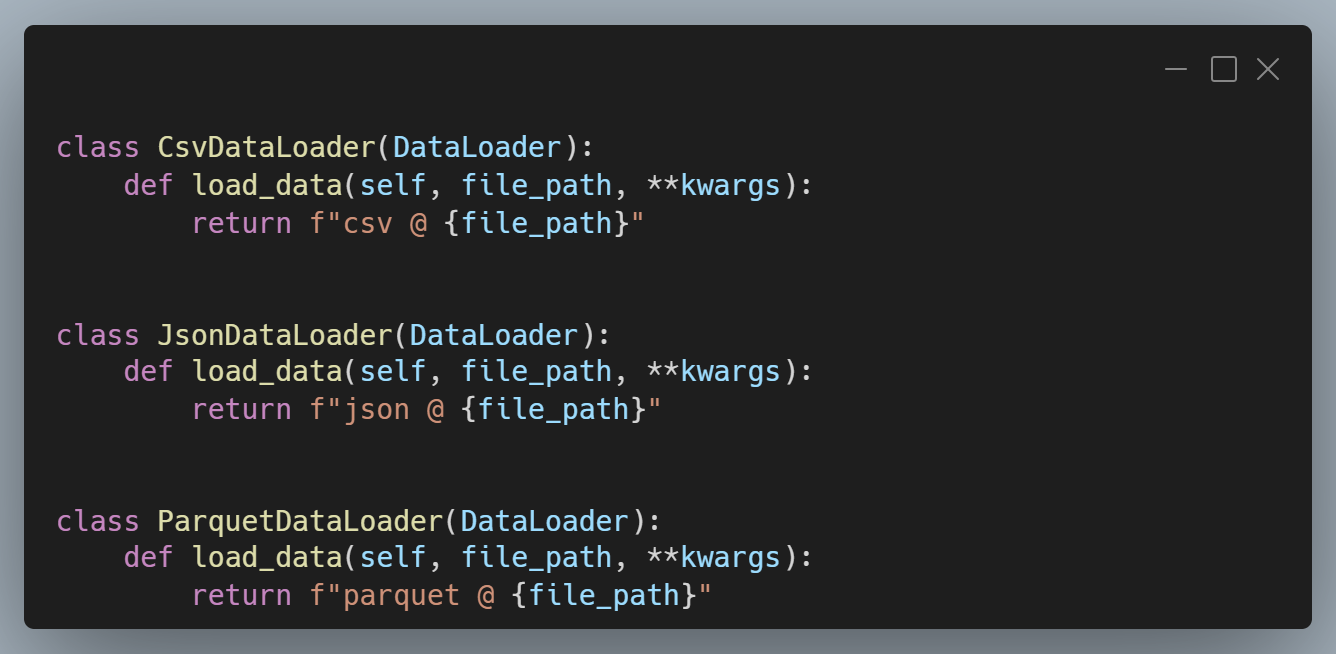

Perfect, now we can implement how each file type is loaded in a subclass, like so:

Now we've implemented very specific classes for each one of our file types, all following the same pattern, which is great. Going back to the structure of the factory method design, we've defined the product/interface (Dataloader) as well as the concrete products (CsvDataLoader, JsonDataLoader, and ParquetDataLoader) in the form of the individual data format-based classes.

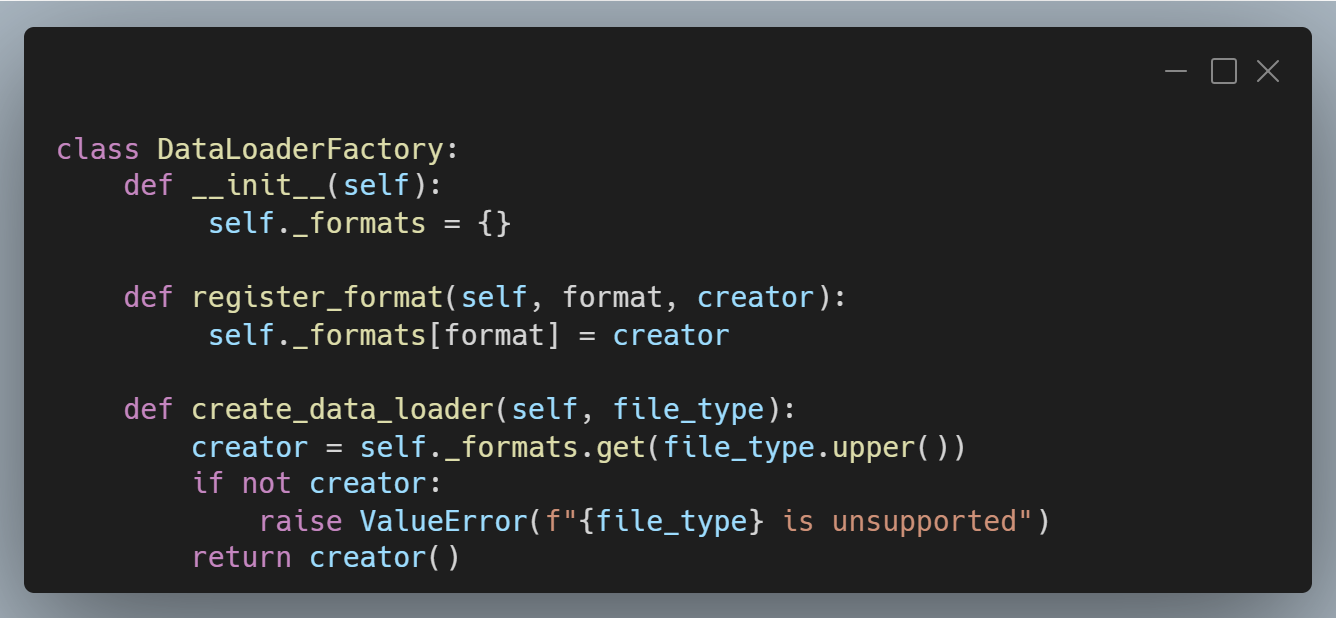

Our "Creator" needs to store the implementation logic of which data loader to return, without needing to return to the creator to add a new data loader. To do that, we'll implement two methods:

register_formatwill allow us to add new formats as we introduce them. This is, in a way, our "concrete creator." Instead of creating creator classes for each one of our products, we are using registration to bind formats to loader classes at runtime.create_data_loaderwill create the concrete product for us.

Our creator, DataLoaderFactory, looks like this.

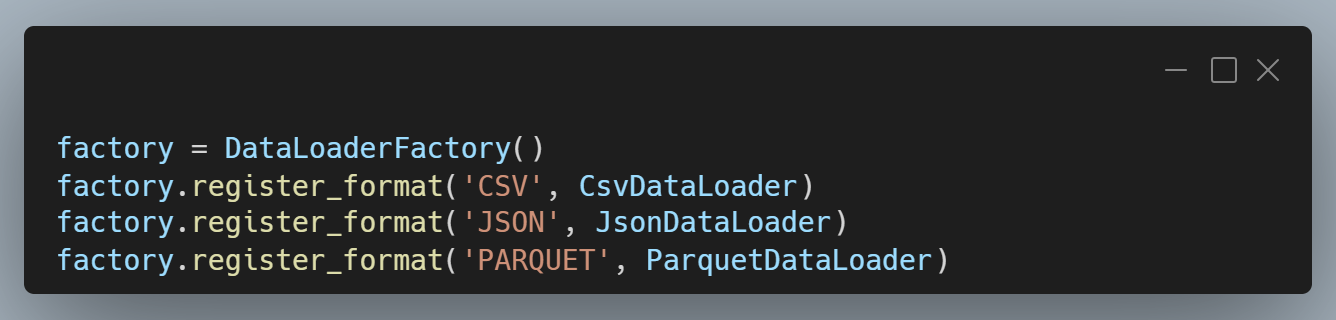

Putting it all together, we can now register formats and assign them creators (classes we created for each product).

Based on the formats we've registered, we can get the product instance using a single class only based on the format of the file.

That's it, a single entry point for all file formats in our data loader, and a single method name to interact with that data!

The next time you find yourself in an if/elif/else chain when you are creating instances of something, consider whether the factory method can help your code be cleaner and more extensible for future needs!